Leisure (Etymology):

Latin - licēre (“Be free/permitted”) => Old French - loisir (“To enjoy oneself”) => Modern English - leisure (“free time”).

Prologue

Leisure is essential to civilization, and in former times leisure for the few was rendered possible only by the labors of the many. But their labors were valuable, not because work is good, but because leisure is good. And with modern technic it would be possible to distribute leisure justly without injury to civilization

- Bertrand Russell

There is a text, parts fragmented and lost to time. De Otio by the Roman philosopher-statesman Seneca the Younger. It pontificates on the most rational, productive and reasonable use of one’s free time. One’s leisure time. Seneca had some lofty ideas, some noble ideals. He wanted us to pursue activities for society’s betterment, for the benefit of people. In our spare time.

I’m sure he was fun at parties, Seneca.

Almost two millennia later the British mathematician-philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote the essay In Praise of Idleness. It championed leisure for humankind.

Bro took an axe to the attitude of work fetishism overtaking the ever-industrializing world in the early decades of the 20th century. He criticised the work-is-virtue mentality preached to the masses since antiquity. He criticized the monopolization of leisure by the privileged, and he saw modern technological progress providing the opportunity to drastically cut working hours for everybody. Scientific organization of the political economy would provide people with ample resources to pursue whatever they wanted without the worry of “making a living”.

Russell observed the world becoming more and more tone-deaf to the value of leisure.

Technological progress continues to make work automated and easier. A.I. has made a revolutionary breakthrough in cognitive labour in recent times. Therefore, leisure is something that should see a net increase across social strata. Instead, job insecurity, automation-induced unemployment anxiety, and the culture of multiple side hustles and the gig economy colour the landscape.

Welcome to the first of a two-part exploration of leisure, its relationship with liberty and the historic trajectory that let the former become a footnote about human well-being, while the latter became an essential metric of human rights.

The history of leisure, and liberty, has always been a political one; where redistribution appears to be one of the most likely and reasonable solutions. But we all know how resistant people are to that. And how inertia bogs down the historic jumps humanity makes towards justice and equity. Leisure (derived from the Latin concept of “being free”) is a resource monopolized by the boujee more than it is available for the broke. Leisure allows you to shape Culture.

Simply having free time isn’t leisure, you get a lot of that in prison including bed and breakfast.

And yeah…I am gonna be reaching quite a bit here. Jumping the gun, making airy connections maybe. Things may get messy.

Anyway…let us go back to a critical juncture in human history when a butterfly must have flapped its wings…

The Epistemic Jailbreak

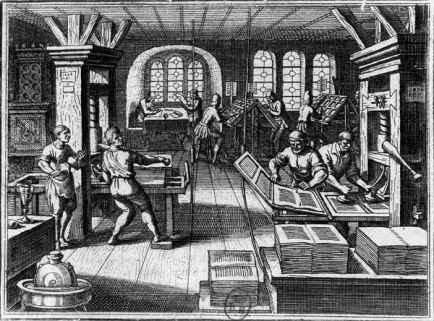

Strasbourg, Europe. 1440: Johannes Gutenberg presents people with his research “Aventuer und Kunst” (Enterprise & Art). It is to do with the work he has been doing on the moveable type-printing press.

The Chinese have had this technology for some time now. But the currents of history are going to make Gutenberg’s work catch on like wildfire.

In his essay, Russell touches upon two points; historically warriors and priests always accrued the surplus and fruits of the peasants’ labour (even in times of famine and war, it was the farmer likely to see starvation rather than the aristocrat); and it was the privileged leisure class (of warriors and priests) who cultivated majority of arts, sciences and cultures.

The first to lose their institutional hegemonic stranglehold were the priests, in a distant corner of the globe.

Kings may have been tyrannical, but they derived legitimacy from God. And God’s clerks ALWAYS enjoyed a hallowed position in society. Their word on “art”, “knowledge” and “value” was sacrosanct. Such was the case with the Brahmins in India, such was the case with the medieval Scholars in the Islamic Golden Age. Such was the case with the Papal Catholic Church of the Vatican.

The “common folk” had their songs, dances and stories; they could be constituted as their leisure activities (in the modern sense of the word). But the ivory-towered clergy (and nobility) decided the canonical culture. The capital C Culture. Everything else, were they to be displeased, could be coined heresy.

But the sacred word was soon to be secularized.

The Justification of Johannes Gutenberg (2000) has a documented exchange between Gutenberg and a priest; the latter being aghast at Gutenberg’s plan to print and distribute the Bible to people. The priest believed that God’s word needed to be interpreted by his lot, that the Bible in the hand of the masses was like “giving a candle to an infant”.

In the coming centuries, the Printing Press steamrolled the orthodox European clergy. The Protestant Reformation employed this new technological innovation to spread its worldview across Europe. Catholic Papal hegemony was broken. With it, a slow democratization ensued. What was a theological breakthrough regarding people having a more personalized relationship with God bereft of institutionalized and corrupt middlemen in the Protestant Reformation was to become the rip current for liberty.

While still patronized by King and Church, Culture slowly finds emancipation. Very slowly. For, even as the reformation turned into the rampage of the 30-Years War between the Protestants and Catholics, the Vatican forced Galileo to censor his discoveries, that Earth was indeed not the centre of the universe. He had perhaps half the leisure, insofar as to study his chosen disciplines. He did not have the liberty to express himself though.

The violence from 1618 to 1648 culminated in the Peace of Westphalia. Many historiographies consider the 16th century (beginning with the publication of Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses in 1517) to be the end of the Middle Ages and the start of the Early Modern Period. The 30-year War was the natural conclusion of the power struggle, essentially for the soul of Europe’s Culture.

But it was also the catalyst for other symbiotic ideas or at least their germination; the decline of feudalism/serfdom, the rise of the free market, the separation of the Church and State, and the Enlightenment and the rise of liberty.

The fate of leisure has always been, and will be, tied to that of its cousin, liberty.

God bless Gutenberg. God bless the printing press. God bless heresy.

Folks become a Nation, Nation becomes a State

The Enlightenment thinkers were the products of their time. Their time involved the beginning of the terminal decline of the old feudal order, and new optimism in human rationality and reasoning. When thinkers Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau worked on ideas of politics and government, or thinkers like Leibniz and Newton worked on the laws of mathematics, or Adam Smith on the laws of economics, they were surfing the nascent but burgeoning wave of reinvigorated intellectual discourse recently freed from the shackles of piety and fealty.

Freedom of expression contested its position in society against the orthodoxy. The centuries since the printing press did not change the fact that it was still a risky business trying to stake your claim in shaping Culture if you were not in the right circles.

The life of Voltaire is emblematic. The man wanted to be a writer, and so he wrote. He satirized French society and religious intolerance in Europe. He is regarded as a champion of tolerance, liberty, reason, and freedom of expression. He was relentless in his ideals.

Best believe the man would have had a podcast, were he alive today.

Voltaire’s writings frequently got him into trouble. He was exiled from France a couple of times, Louise XV banned him from the city of Paris at one point; whereas Frederick the Great of Prussia had at one point admired and invited him to stay at the Prussian court, but they had a lover’s spat due to Voltaire’s unfiltered opinions. He had to flee.

His writings were often censored. Books banned. But that didn’t impede their contagion. The publishing industry had turned out to be a different kind of beast. If France banned Letters Concerning the English Nation, then it would find publishers in Britain. And the copies would find their way back across the Channel.

There was a free market of trade, commerce and industry weaving itself around the world. It gave rise to something like the career of a “writer”. Ofc, there were scribes before, but they usually relied on patronage (royal or religious), or they were like a side hustle. Now, theoretically, one could solely trade in writing their thoughts and ideas.

Self-expression could be disseminated into the public ether like never before in history.

Like all things, though, one required resources. It is a known fact that Voltaire and the mathematician Charles-Marie de La Condamine rigged the French lottery system to become filthy rich for the rest of their lives. Cash flow was not his worry ever again.

So he definitely had leisure as defined in the narrow contemporary sense of “free time” from earning a living. Did Voltaire have the liberty to write what he wanted? Or did he carve it out? Can we say that he had the leisure to become a writer and write whatever he wanted, rather than self-censor and tiptoe around patrons? Leisure as “licere” or the Latin for “being free”.

A natural culmination of what historians call Europe’s “Age of Enlightenment”; the unravelling cultural hegemony of those Bertrand Russell called “warriors and priests”, or the nobility and the clergy led to new ideas of sociocultural organization of people. Everybody had a stake in society now; everybody’s voice, at least in theory, was valid. Everyone had a say in shaping Culture. People discussed The Social Contract; whereas it was the King’s sword or the Priest’s sermon that justified the social order hitherto, now it was a slow meticulous discourse and reasoning.

Albert Camus’ The Rebel (1951) charts the genealogical history of rebellion in Western (European) thought. Rebellion against the status quo, rebellion to find moral and ethical absolution.

He notes the titanic impact of the French Revolution on history. Two and half centuries of the Press, of social re-ordering and fragmenting religious authority, had not been enough to dethrone the monarchy. Then in 1789, the people rose against governance by the grace of God and his agent on earth the king. They didn’t want to be ruled by Grace.

They wanted the rule of reason. Or, as Camus put it, The Social Contract placed a new God in the order of things - reason; and its representation on Earth was the General Will of people. Reason was the equalizer of all people, at least in theory.

The emerging paradigm of the nation-state became the bastion of the General Will, the Volonte Generale. Which, again, in theory, meant liberty, meant freedom of expression for all.

Pandora Opens Her Box of Human Expression

Britain, September 1929:Virginia Woolf writes: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

Voltaire had got himself both all those years ago.

She wrote the book, based on two papers presented at Cambridge University with the theme being “Women & Fiction”. But A Room of One’s Own (1929) is so much more. It is a treatise on historical material conditions constraining one group of people (in this case the female sex) from pursuing any enterprise at all. Particularly the hallowed enterprise of self-expression, so jealously guarded by the “warriors and priests” in the past.

Virginia is a savage critique. A literary Miranda Priestly. She saw the pioneers of women’s English literature as having produced a mixed bag of work. She praised Jane Austen’s work -her final execution of it - she praised Charlotte Bronte’s natural pen game but thought her writing too rooted in her background and conditions.

Her central critique:

The historic constraint on leisure and liberty, for women, resulted in works of literature shorted off their full potential. Pioneers like Jane Austen and the Brontes focused on things they knew, and the powers-to-be ensured they didn’t know about much - save for how society got down with marriage, courtship and kitchen. And they did their best with that. Shakespeare, the GOAT, had full liberty of perfecting his work. And for Virginia, this freedom and access to experience and knowledge of life far greater than any woman of his time, allowed Shakespeare’s body of work to be diverse, complex and of a more universal calibre.

Jane Austen and Charlotte Bronte excelled with what they had. But compared to Shakespeare they weren’t given much of a chance.

By the time of her writing though, things had changed. Enlightenment had given birth to Modernity. Women in Britain got the right to vote; almost every adult in the country now had the right. They were entering the workforce. New industries, jobs and careers for contemplation; and while the ceiling was glassed, one could at least look through and envision the ever-increasing possibilities brought about by Modernity.

Culture industrialized, as Messers. Adorno and Horkheimer would complain. They raised concerns about the vapidity, superficiality and greedy market-driven logic corrupting Culture - the soulless mass production of movies, songs, art, literature etc.

However, this very industrialization created a whole lot of liberty for people. During Gutenberg’s time, most people were in bondage and serfdom, forced to work on the land. They couldn’t just pack up and leave to try their hands at other things. Urban centres perhaps had more opportunities, but even there one had to know the correct people and networks to get to do what they wanted.

Now one had the option of becoming a professional athlete, movie star, musician, scholar, engineer, doctor, lawyer and all that. Ofc, it depended upon your circumstance and resources. But the law of the land wouldn’t stop you from trying. If you left your family in the country to go contend your luck in the city, rest assured you wouldn’t find them whipped and flayed by a feudal lord for your ambition. Bonded labour wasn’t as much of a social problem as unemployment.

Now that has to count as liberty.

India, September 1929: Democracy is on the ascent to becoming undeniable.

British colonial rule is terminally ill. The Indians know of Print, Radio, and Film. Dadasaheb “the Daddy of Indian Cinema” Phalke had brought movie-making technology before the First World War itself.

The country, never united historically if not under the sword, was developing a shared public consciousness with mass media and the notion of national self-determination. Newspapers, pamphlets and books started circulating. Speeches on the radio and films on the screen all look to create a new rendition of Culture. Writings about impending national self-determination are all the rage.

The paradigm of The Social Contract made national-self determination undeniable. People had to consent to the state. The General Will of the people implied the right to choose. Despite all the mental gymnastics done on grounds of cultural differences (superiority vs inferiority) and gendered grounds, the logical conclusion of members of all races, cultures and genders being entitled to their own self-expression and liberty was becoming irrefutable.

Countries beyond Europe experienced the Modernist paradigm through the force of Imperialism. But the raw awesome power of this paradigm seduced everybody. They wanted to experience it on their terms. The Printing Press, and its descendants - Mass Media. All the other industrial technological innovations. Along with the Enlightenment. Latent in these developments - the liberation of human expression.

If imperialists used these developments on colonized countries to extract and extort material benefits for the colonizing nations, national self-determination would give them the liberty to harness these technological, scientific and sociopolitical developments for their self-actualization.

But what about leisure?

Epilogue

If you have a room of your own and money, you sure as hell could get yourself some leisure time. By the 1920s and ‘30s, we have professional sporting events, the Cinema, concerts and music halls to be enjoyed by the public. Gramophones and radio.

A new concept of “leisure” is being shaped; becoming synonymous with rest n’ recreation. R n’ r. There had always been “high” and “low” cultures, aristocratic and folk cultures. But mass media and the General Will (of the people) now created a composite popular culture - popular movies, music, plays, books and celebrities.

In his essay, In Praise of Idleness, these are what Bertrand Russell identifies as passive consumptive leisure activities. The R n’ r types. And there is absolutely nothing wrong with them. However, the circumstances that bring about such activities may be of some fault.

Russell observed that all the technological progress wasn’t actually leading to more Leisure for most. Working hours in the industrial world remained high, despite productivity reaching a different galaxy compared to those countries still mostly feudal at his time. He pointed the fault at the increasing fetishization of work and productivity.

What sociologist Max Weber called the Protestant Work Ethic that dominated the Northern (Protestant) European nations that were the first to industrialize, now increasingly dominated all industrialized, and industrializing societies. The ethic became a pathology coded in Modernity, and it cleaved the cousins apart.

Leisure never was the centre stage of attraction throughout the discourses of the Enlightenment and Modernism. It was always liberty. The incessant weight and importance put upon the latter, and the fundamental misunderstanding of the former as some sort of indulgent free time - rather than a serious abstract freedom allowing for experimentation, innovation and creation - snapped the two.

And soon enough liberty would reach a glass ceiling. Unable to break forth to the promised utopia, no matter how hard the gears grind, no matter how industrial the spirit churns.

Because it left its cousin behind.

This piece has been a lot. Trying to cover a large breadth undoubtedly affects the depth. But such is the historical survey of leisure and liberty’s trajectories. Each point deserves a more in-depth dissection, but there must be a book or a study doing so. This is a scrambled egg kinda exploration. We’ll do some more jumping picking up from where we left behind in Part II.